We asked author Ali Ezzatyar to tell us about his new book, The Last Mufti of Iranian Kurdistan: Ethnic and Religious Implications in the Greater Middle East. What follows are his reflections on the origins of the book as well as its main themes. Why is it important to understand Kurdish nationalism and the life of Ahmad Moftizadeh? Can we better understand the underlying causes of conflict and extremism in the modern Middle East by looking back at the important events of the 20th century? Read on.

____________________

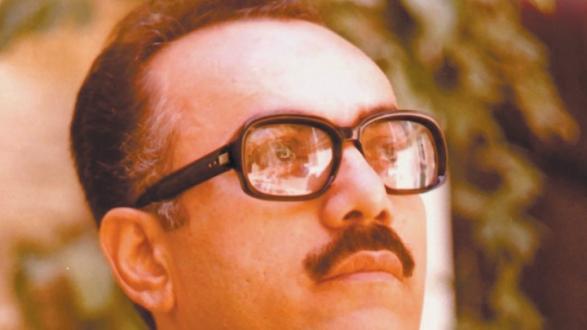

I first learned about the improbable character of Ahmad Moftizadeh while traveling through Iranian Kurdistan 15 years ago. Even in the days prior to September 11, 2011, his profile seemed unlikely: an orthodox Sunni scholar with the rank of "mufti" who was comfortable with the notion of Kurdish nationalism, but was also socially progressive and devoutly nonviolent. The story went on that he was the person with the single largest following in Kurdistan and Sunni Iran during the revolution. He at first cooperated with the new regime in its early days, until it began to renege on its promises to the Kurdish people.

I thought to myself that this character did not likely exist as described. As is typical for partisan members of political movements, I figured his profile was exaggerated and embellished. After all, how could I and the world have not heard of him before? I could not find many references to him online or in the library, but I also did not find anything that directly contradicted the rather lofty description of him. I knew that if such a character did exist, he had an important story to tell. With time, it became clear that my initial skepticism was misplaced.

This book is separated into three sections. The first is a primer on the emergence of Kurdish nationalism and its relationship with other forms of nationalisms and Islamism. It covers a number of important Kurdish movements and draws conclusions from them, leading into the biographical section:

"Overt expressions of Kurdish nationalism became widespread through the year 1945, and against the backdrop of a new sense of identity that captivated the region, a notable from the city of Mahabad gave a stirring speech in November of that year. In his delivery at the Cultural Center of Mahabad, he announced that the Democratic Party of Kurdistan (KDPI) replaced a soon-dissolved Party for Kurdistan Revival, and that Kurdish self-rule was now the official platform of Kurdistan. In January of 1946, after the remaining vestiges of central government bureaucracy were chased out of Mahabad, Qazi Muhammad announced the establishment of the Mahabad Republic. For all intents and purposes, Muhammad had established an independent Kurdish nation-state for the first time in history."

The biographical portion of the book is by far its most robust because Moftizadeh’s is a fascinating story that demonstrates the complex spiritual and political makeup of Iranian Kurdistan. This portion was compiled through research in four languages, most of it original. A number of Moftizadeh’s supporters, as well as his most ardent opponents within the Kurdish community, were interviewed. The story also adds context to the history covered in the first part of the book:

The biographical portion of the book is by far its most robust because Moftizadeh’s is a fascinating story that demonstrates the complex spiritual and political makeup of Iranian Kurdistan. This portion was compiled through research in four languages, most of it original. A number of Moftizadeh’s supporters, as well as his most ardent opponents within the Kurdish community, were interviewed. The story also adds context to the history covered in the first part of the book:

"As he discussed this nuanced view of a long-gone acquaintance, he interrupted one of his thoughts on an unrelated question, and paused. 'You know I am being taped. They have this phone, and my downstairs phone, and my mobile phone bugged. You know that right?... They are listening to everything we have been saying. You can imagine that they probably don’t like a lot of what they’re hearing, right?... But I’m not afraid. I am not afraid to speak, not even a bit. Do you know why?' And Mr. Rohani continued, his tone of voice encumbered by the heavy weight of nostalgia, after days of reflection and discussion about Moftizadeh’s virtues, the traps he fell into, his hours yelling into the night from his hospital bed in pain… 'because Kaka Ahmo’s taught me not to be afraid.'"

The final part of the book is forward looking. It takes a fresh look at the Middle East region with the benefit of the historical context and conclusions in the prior sections, and argues for a recalibration of the interest calculation for the world’s democracies.

As Islamist movements gain strength, Kurdish parties (with their varied ideological compositions) are likely immunized from similar trajectories.

"The nature of Iraqi Kurdistan’s dependence on its major parties is a debilitating factor, and when push comes to shove, the main Kurdish parties need to demonstrate that they value Kurdistan’s long-term democratic health more than the prosperity of their respective parties. The United States in particular has an essential role to play in mitigating disputes between Kurdish parties with the hope of encouraging the continued democratic nature of the Kurdistan region. Supporting a stable and strong Kurdish leadership to help fight the Islamic State is reasonable, but not at the expense of the Kurdish region’s pluralism."

Through a journey into the life of Moftizadeh and a revisiting of important 20th century events, the book argues that Kurdish nationalism and Islamism have an inverse relationship. This theory has wide reaching implications. As Islamist movements gain strength, Kurdish parties (with their varied ideological compositions) are likely immunized from similar trajectories. It also follows that they make practical and reliable allies against such groups, and, as Sunni Muslims, have trendsetting potential. An equally important but separate conclusion that can be drawn from the book's biographical portion is that orthodox Islamic thought is compatible with progressive ideals, such as the empowerment of women and nonviolence.

____________________

Ali Ezzatyar is a lawyer, U.S. diplomat, and a member of the Pacific Council. Prior to joining the Foreign Service and the U.S. Agency for International Development, he practiced law at a number of prominent international firms and served as executive director of the Center for Entrepreneurship and Development in the Middle East at the University of California, Berkeley. Follow him on Twitter @ezzatyar.

Views expressed in the book and by the author do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Government of the Pacific Council.