Background

From January 7-10, 2020, I participated as an observer sponsored by the Pacific Council at the pre-trial proceedings involving the U.S. prosecution against Abd Al Rahim Hussayn Muhammad Al-Nashiri, the alleged orchestrator of the boat bombings in 2000 of the USS Cole and in 2002 of the M/V Limburg. Al-Nashiri has been charged with multiple capital offenses, including murder in violation of war and terrorism laws, and the United States seeks the death penalty as a result.

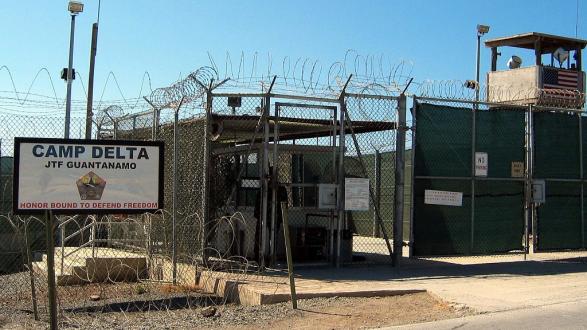

The hearings took place against a complicated historical and procedural backdrop. As more fully described in In re Al-Nashiri, USCA Case No. 18-1315 (DC Cir. 2019), Al-Nashiri was captured in 2002. He then spent four years at various CIA “black sites” where he was allegedly tortured. He was subsequently transferred in 2006 to the terrorist brig at Guantánamo Bay where he has been held ever since.

Al-Nashiri was formally charged in 2011 after the convening of the second, and current, Military Commission established to try the various Guantánamo Bay detainees. In 2014, Air Force Colonel Vance Spath began presiding over the Al-Nashiri proceedings. Over the following four years, Judge Spath made numerous pre-trial rulings in the case.

During this time, Al-Nashiri was represented by a defense trial team led by Richard Kammen, a civilian learned expert in death penalty cases who had been on the team since 2011, along with Mary Spears and Rosa Eliades, civilian employees of the Defense Department. Lt. Alaric Piette, a Navy JAG officer with then limited legal experience, was detailed to the team in 2017.

Al-Nashiri has been charged with multiple capital offenses, including murder in violation of war and terrorism laws, and the United States seeks the death penalty as a result.

In 2018, two events dramatically changed this landscape. First, Judge Spath was selected by then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions to fill an open immigration judgeship in the Justice Department’s Executive Office for Immigration Review. As it turned out, however, Judge Spath had applied for the job as early as 2015, but had not disclosed the fact to any of the Guantánamo Bay litigants. Second, the defense team learned that the conference room which they used to meet with their client in 2017 was outfitted with a listening device that, if turned on, would allow U.S. government officials to overhear their attorney-client conversations.

The defense team filed two motions as a result. The first sought to vacate all rulings of Judge Spath going back to his appointment in 2015 on the grounds of conflict of interest. The second requested permission for attorneys Kammen, Spears, and Eliades to withdraw as counsel for Al-Nashiri on the grounds that, given the presence of the listening device, the attorneys could not maintain confidentiality and, thus, could not fulfill their ethical obligations to their client.

Over the course of various hearings and proceedings in 2018 and 2019, both motions were granted and ultimately upheld by the D.C. Circuit in its 2019 opinion in In re Al-Nashiri. Id. As a result, the proceedings I observed took place before a new judge, Army Col. Lanny Acosta, Jr., who had been on the case only three months. Other than Lt. Piette, Al-Nashiri was represented by a new defense team, including a new lead counsel/learned expert, Tony Natale, who had been representing Al-Nashiri for only a matter of months.

Motions

Over the course of my observer week, the Commission judge heard a number of motions brought by the defense. All were based in whole or part on the events described above. The motions included the following:

Motion to dismiss case/death penalty

The defense’s first motion was to dismiss the case in its entirety, or at a minimum dismiss the death penalty demand, based on a theory of “structural error” due to the prosecution’s alleged “constructive severance” of the attorney-client relationship between Kammen, Spears, and Eliades and their client Al-Nashiri. The defense argued that Al-Nashiri was entitled to 6th Amendment rights to effective assistance of counsel and that, by placing a listening device in the attorney-client conference room, and subsequently refusing to provide defense counsel with documents and other evidence indicating the extent to which attorney-client conversations were overheard by the government, the government had effectively and intentionally severed the attorney-client relationship.

Under various case law, including In re Spears, this constituted a per se violation of Al-Nashiri’s 6th Amendment rights. The defense further argued that, given that Kammen was Al-Nashiri’s chosen counsel with close to 10 years of experience on the case, the prejudice to Al-Nashiri in losing Kammen’s services was incalculable and incapable of remedy. Thus, the only appropriate sanction is dismissal of the entire case against Al-Nashiri or, at a minimum, elimination of the death penalty threat.

The prosecution argued that Al-Nashiri is not entitled to 6th Amendment rights in the Military Commission.

The prosecution opposed the motion, arguing that there was no record evidence to justify a finding that Kammen had good cause to withdraw. In that regard, the prosecution asserted that Al-Nashiri and his attorneys used the room only on one occasion and that there had been no actual or attempted bugging of their conversation. Rather, per an “allowable [i.e., unclassified] statement” issued by the government, there had only been a single “unintentional overhearing” incident and that incident involved other detainees; moreover, the eavesdroppers were CIA agents, not prosecution counsel.

The prosecution further argued that Kammen’s relationship with Al-Nashiri had not been severed as a factual matter. Specifically, Kammen’s contract had been extended through 2020 and that Kammen was still consulting with the defense team. Further, it was Kammen who had voluntarily absented himself from the current proceedings, and Kammen who “self-created” the would-be ethical dilemma related to the listening device. In that regard, the prosecution suggested that Kammen’s real motive may have been to delay and frustrate the proceedings.

Finally, the prosecution argued that, even if there had been an improper severance, Al-Nashiri is not entitled to 6th Amendment rights in the Military Commission.

Motion to extend contract of defense counsel Air Force (AF) Major Robinson

The defense’s next motion was to extend the contract of defense counsel AF Major Robinson for two years. The defense argued that Robinson was a key member of the defense team, functioned as “commanding officer” of the team from his station in Washington, D.C. Robinson, however, was a reservist with only approximately six months of reserve duty left to serve. More than six months ago, the defense had requested that the AF approve a two-year extension of Robinson’s contract to participate on the team.

However, as of the time of the hearing, the defense team had yet to receive any response. The defense team was concerned that, if the AF did not act before Robinson’s reserve term expired, Robinson’s services would be lost. Should this occur, the government would be responsible for yet another severance of the attorney-client relationship in violation of Al-Nashiri’s 6th Amendment rights. To avoid this violation, as well as yet another event that would delay Al-Nashiri’s trial, it was imperative for the Commission judge to step in and order Robinson’s contract to be extended.

The defense’s next motion was to extend the contract of the defense’s medical examiner so as to allow her to visit Al-Nashiri up to four times, and spend up to 80 hours, per year for each year through and including his trial, all for the purpose of providing comprehensive medical exams of Al-Nashiri, since Al-Nashiri was tortured by the government and suffers from severe PTSD.

The prosecution opposed the motion, stating that it has no objection to the extension of the contract, but questioning if the judge had the power to order the AF to extend the contract. The prosecution argued that it was best to wait to see what decision the AF makes, particularly since, per various case law, a separation of Robinson from the defense team due to the fact that his reserve time is up would not constitute an improper severance.

Motion to extend contract of defense medical examiner, Dr. Crosby

The defense’s next motion was to extend the contract of the defense’s medical examiner, Dr. Crosby, so as to allow her to visit Al-Nashiri up to four times, and spend up to 80 hours, per year for each year through and including his trial, all for the purpose of providing comprehensive medical exams of Al-Nashiri and consulting with the defense team as to her findings. The defense argued that Dr. Crosby’s services were relevant since Al-Nashiri was tortured by the government and suffers from severe PTSD; further, that the effects of his torture can be introduced in mitigation since this is a capital case. Thus, Dr. Crosby’s services are critical to the defense.

Moreover, since the relevant medical condition will include Al-Nashiri’s condition at the time of trial, Dr. Crosby’s services are needed throughout the pre-trial and trial period. The defense indicated that Dr. Crosby’s contract had first been approved in 2012 and had been extended most recently in 2018. However, only eight more hours were remaining on the contract. Defense counsel had requested additional authorization from the convening authority (i.e. the Secretary of Defense) but had received no response. As such, similar to the situation involving AF Major Robinson, it was incumbent on the judge to act on the matter to guarantee Al-Nashiri’s rights.

The defense’s next motion was to compel the government to provide Al-Nashiri a laptop computer to assist him in the review of documents. The prosecution opposed the motion, arguing that no case law indicates a defendant to be entitled to a laptop.

The prosecution opposed the motion as unnecessary and inappropriate for the judge to decide. Among other things, the prosecution argued that Dr. Crosby already had provided 320 hours of service since her original engagement and that 23 (not eight) hours were left on her current contract. The prosecution also argued that Dr. Crosby was providing inappropriate therapeutic services, such as providing comfort services to Al-Nashiri during an MRI examination.

The defense responded that Dr. Crosby was not attending the MRI examination to provide comfort to Al-Nashiri, but instead to observe his behavior as part of her PTSD analysis. While arguing that the convening authority, not the judge, had to decide the matter, the prosecution indicated that it had no information as to when the convening authority might do so.

Motion to compel provision of a laptop computer

The defense’s next motion was to compel the government to provide Al-Nashiri a laptop computer to assist him in the review of documents. This issue was the topic of one of the “legacy motions” heard by Judge Spath but invalidated by the D.C. Circuit. Per the defense, the government had produced approximately 230,000 documents in the case.

While it was reasonable for the government to produce the documents in electronic fashion, it was not reasonable to deny Al-Nashiri access to a laptop to review them. Hard copies of the documents would fill 75 feet of bin space, much more than would fit within Al-Nashiri’s cell. Thus, a laptop provided the only means by which, as a practical matter, he could access all the documents. Further, it was the only means by which Al-Nashiri could consult with counsel about unclassified documents when counsel was not present at Guantánamo. (Classified document could only be reviewed when counsel was physically present.)

All other accused’s at Guantánamo had laptop access, and Guantánamo had security protocols in place that served to guard against security breaches. Finally, the convening authority already had approved purchase of the laptop. For all these reasons, provision of a laptop was necessary to ensure Al-Nashiri’s 6th Amendment rights.

The defense next moved to continue all substantive motions and other matters until at least December of 2021. The prosecution argued that the judge should set a trial date or other deadline to force the attorneys to focus and get ready in an expeditious manner.

The prosecution opposed the motion, arguing that no case law indicates a defendant to be entitled to a laptop. It acknowledged that the 9/11 defendants had received laptops, but that this occurred when they were all representing themselves and was reasonable for that reason. Once the defendants obtained outside counsel, the government allowed the defendants to keep the laptops to help facilitate the new attorney representations.

However, recently there had been security problems with the defendants’ use of the laptops, leading the government to take back all but one of the laptops while the situation is being investigated. (The prosecution acknowledged that one or more of the defendants have filed motions seeking return of the laptops.)

The prosecution further argued that, if Al-Nashiri did not have physical access to all non-classified documents, that was not the government’s fault since the government provided all such documents to defense counsel with the understanding that defense counsel will then provide the documents to its client. Finally, the government stated that it had no knowledge of the convening authority’s would-be approval of the purchase of the laptop.

Motion to continue all substantive motions and matters until December 2021

The defense next moved to continue all substantive motions and other matters until at least December of 2021. The motion was argued by Al-Nashiri’s new learned and lead counsel, Tony Natale. Natale, who resides in Miami, Florida, argued that, as lead counsel, he is responsible for the entire defense team and strategy. He has been on the team only a matter of months and still needed to learn the case and develop a meaningful attorney-client relationship with Al-Nashiri.

Moreover, given the D.C. Circuit’s ruling invalidating all rulings by Judge Spath, the case essentially was restarting from scratch. In addition to his need to become familiar with the court record (much of which can only be reviewed in Washington, D.C. or Guantánamo), the Commission rules, and the idiosyncrasies of traveling to and litigating at Guantánamo, Natale needed to conduct additional investigation, including abroad, into the extent of the government’s torture of Al-Nashiri. He also needs to find new mitigation and other experts, as well as replace key members of the defense team.

For example, appellate specialist Capt. Mizer had asked for permission to leave the team when his tour of duty ends in March 2020. And, as noted, the status of Major Robinson is unclear. For all these reasons, he needs an abeyance of substantive motions for two years to allow sufficient time to get up to speed and, thus, provide effective assistance to his client.

No ruling appears to have yet been made on the defense motion to continue all substantive motions until December 2021.

The prosecution opposed the motion on various grounds. It noted that only seven weeks of court time was scheduled for the case in 2020, leaving 44 weeks for other preparation. Moreover, the only motions to be heard in 2020 were the legacy motions ruled on by Judge Spath. Other members of the defense team were well-versed in the record and could assist Natale on these matters. Further, the vast majority of the documents in the case are unclassified and can be reviewed at any location.

The defendant has no right to a “meaningful relationship” with his counsel, only to competent counsel. And, the 6th Amendment does not apply in Commission proceedings in any event. For all these reasons, the motion should be denied. Instead, the judge should set a trial date or other deadline to force the attorneys to focus and get ready in an expeditious manner.

Motion to compel discovery regarding listening device incident

The final motion made by the defense was to compel the production of additional documents concerning the listening device incident. The defense argued that the prosecution had yet to provide documents or other evidence requested by the defense reflecting the government’s purported investigation of the listening device incident. Since the facts of this incident were critical to the defense, including its motion to dismiss (see section A above), the judged needed to intervene and order the production.

The prosecution argued that, since the government did not actually listen in on any conversation between Al-Nashiri and his attorneys, there were no additional documents to provide. Further, the investigation of the incident was not being conducted by the prosecution but by a separate government agency (ostensibly the CIA) over which the prosecution had no power or control. The prosecution indicated that it would be helpful if the judge, who would be more influential than the prosecution with the other agency, set a deadline for production of the documents.

Rulings

In recent weeks, Commission Judge Acosta has issued the following rulings:

A. The defense motion to dismiss based on alleged structural error is denied since attorney Kammen could have, but did not, return voluntarily as counsel; also since defendant has no right to require his return, especially since he continues to enjoy the assistance of five highly qualified counsel. (On a related note, Capt. Mizer’s request to withdraw as counsel when his tour of duty ends in March 2020 is denied.)

B. The defense motion to extend Major Robinson’s contract is deferred since the judge doubts he has the authority to order the extension. Instead, the parties are ordered to meet and confer and file joint status reports every 30 days re: Major Robinson’s status and the expected time for disposition of his request for extension.

C. On the defense motion to order the provision of a laptop, the government is ordered to provide defendant the ability to review discovery in the format in which the government chooses to provide it. Whether that is a laptop computer, a desktop computer, or some other means is not up to the Commission to decide. To the extent the defense motion specifically requests a laptop, it is denied.

D. On the defense motion to compel discovery re: the listening device incident, the government is ordered to comply with relevant discovery orders by January 31, 2020.

The judge also issued a ruling on the defense motion to extend the contract of defense medical examiner. However, the ruling is still under review and, thus, not yet public. No ruling appears to have yet been made on the defense motion to continue all substantive motions until December 2021.

_______________________

Philip Recht is a Pacific Council member and a Los Angeles Partner at Charge, Mayer Brown LLP.

Learn more about the Pacific Council’s GTMO Observer Program.

The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Pacific Council.